Nojoqui Tarantula Migration DxPeditions

The Annual Nojoqui Tarantula

Migration Dxpedition: Each year, thousands of tarantulas

brave countless dangers as they migrate to their ancestral breeding grounds

somewhere in northern Santa Barbara county. The journey, which is believed

to span some 50 miles across treacherous terrain and several county highways,

is one of the most unusual mass migrations. Once

thought to be only myth, the Nojoqui Tarantulas have recently been rediscovered

and their great migration the source of scientific wonder and amazement.

Thought to be related to the Amazon tarantula, the Nojoqui

tarantula's origins are unknown. Stories past down from Nojoqui locals

depict a series of strange and mysterious events related to the annual migration:

- In 1864, the rotting remains of a herd of cattle

that happened to wander into the migration path, were found nearly

completely consumed. Once thought to only consume leafy green

vegetable matter, it is believed that the tarantulas went on a feeding

frenzy prompted by an usually dry summer that depleted the local fauna.

- In 1912, thousands of tarantulas were found crushed

and buried in a landslide that occurred during the night of the migration.

A fierce thunderstorm caused one of the hillsides in the migration

path to give way burying thousands of tarantulas under tons of debris. There

had been no reports of thunderstorms or landslides in the area either before

that night or since.

- In 1947, a local rancher installed an electric fence

along his property. The fence happened to be in the migration path that

year. The tarantulas attempted to cross over the fence by building

a bridge with their bodies. The increased load on the electrical system

ignited fires along the fence and the local electrical substation, plunging

the entire central coast of California into a blackout and igniting one

of the largest brush fires in Santa Barbara history.

This year, we have good information on when and where

the migration will occur. Local Nojoqui's who claim to know, have told

us that this year's migration might be the largest in numbers of the past 50

years. Over the past several years, migrations have been dwindling, prompting

some scientists to speculate that the Nojoqui tarantulas might be perilously

close to extinction. Locals have told us that building development near

the breeding grounds may be responsible for the recent decline.

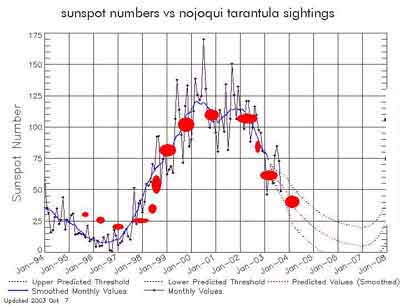

However, upon further examination, I have found that the

sightings of mass numbers of migrating tarantulas closely follows the sunspot

cycle. Most amateurs will quickly recognize the graphic on the left. The

red dots indicate the relative size of recent tarantula migratory numbers superimposed

on the sunspot cycle as reported by NOAA in Boulder Colorado.

Clearly, with only limited empirical data, further study

must be undertaken to determine if there is a link between the xray solar flux

and the migration patterns of the Nojoqui tarantulas. But the graphic

seems to imply that the locals might be wrong in their assessment of

current tarantula numbers. If the data is correct, this year's migration

should be approaching the low numbers of 1997 and not the massive event

that has been talked about in recent weeks around Nojoqui.

We have not yet obtained the necessary permitting. We

do not want to attract hundreds of observers for fear of putting unsuspecting

tourists in harm's way. We certainly do not want a headline in the local

papers linking our hobby to a series of unfortunate incidents during the migration.

So, we just might go in under the radar and set up just after any initial

sightings of the migration are reported.

PRIOR SCIENCE

No, your eyes aren't playing tricks on you. Yes,

that's a radio antenna attached to this male tarantula. Actually, it's

a favorite among tarantulas: Aphonopelma Hentzi (ARANEAE, THERAPHOSIDAE),

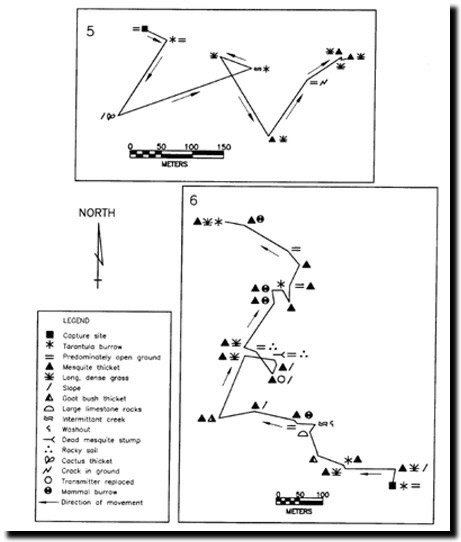

a male brown tarantula. In 1999 a study was conducted to gain insight

into the migratory life history component of the male brown tarantula, Aphonopelma

hentzi (shown above), and to determine if radio telemetry could successfully

answer questions regarding the ecology of theraphosids. Tarantulas were equipped

with radio transmitters and their movement monitored using an antenna and radio

receiver. Overall movement of males was in all directions and randomness could

not be excluded as a factor. Individual males moved relatively large distances,

up to 1300m, and significant directedness was only found in three individuals.

Later

it was discovered that these three unique theraphosids were actually once the

personal property of Phoenix resident Johnny Saulisco. Young Mr. Saulisco

apparently grew tired of his three pets and released them back into the wild

approximately a year before the study. Apparently, Johnny used the three

in a science fair project entitled "Do Tarantulas Have A Trial and Error

System?" He had devised a series of mazes the tarantulas needed to

navigate in order to get to the female tarantula. There were six choices

in the form of paths leading to six chambers wherein the female lay. However,

Johnny only put two females and four other males in the six rooms. He

repeatedly tested his pets. Frustrated that they didn't seem to figure

it out, he concluded the answer was "no" and later released them back

into the wild. Later

it was discovered that these three unique theraphosids were actually once the

personal property of Phoenix resident Johnny Saulisco. Young Mr. Saulisco

apparently grew tired of his three pets and released them back into the wild

approximately a year before the study. Apparently, Johnny used the three

in a science fair project entitled "Do Tarantulas Have A Trial and Error

System?" He had devised a series of mazes the tarantulas needed to

navigate in order to get to the female tarantula. There were six choices

in the form of paths leading to six chambers wherein the female lay. However,

Johnny only put two females and four other males in the six rooms. He

repeatedly tested his pets. Frustrated that they didn't seem to figure

it out, he concluded the answer was "no" and later released them back

into the wild.

Apparently, the limited exposure to a learned environmental

response in captivity was enough to differentiate the behavior between domesticated

and wild tarantulas in a blind test.

Fearing the contamination of the local tarantula gene

pool by human forces, the Phoenix County Board of Supervisors adopted a "no

release of captive theraphosids" or any other 'desert pets' back into the

wild policy. "We've seen what can happen when human planted grasses

invade the hillsides. We're not going to let that happen to our tarantulas

and other desert local populations."

It appeared that this policy was successful in averting

an ecological disaster, based on the levels of tramatic compaction syndrome

seen on the local roads and highways in and around Phoenix.

TARANTULA

MIGRATION INTERVIEW ON KYTD RADIO

2006

Migration

|

Get

your official 2008 Nojoqui Tarantula Migration stuff

here!

Get

your official 2008 Nojoqui Tarantula Migration stuff

here!